By Christina Catanese, Director of Environmental Art

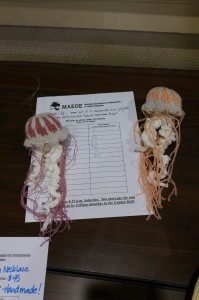

I recently had the opportunity to attend a great conference, the annual gathering of the Maryland Association for Environmental and Outdoor Education (MAEOE), which this year focused on the theme of integrating the arts into environmental education.

The conference occurred on February 4th, but the beginning of this story actually goes back to January 2015. At the time, the idea of an arts-flavored conference for environmental educators was just a glimmer in the eye of John Sandkuhler, a MAEOE board member who had long been involved in organizing the MAEOE conference. John reached out to me early in their process of proposing this idea, to talk about how we at the Schuylkill Center had integrated environmental art into our programming and to pick my brain about potential artists and organizations that could be involved in the effort. Together with his daughters (who are also variously involved in the arts and environmental fields), we had a great winter afternoon chat about the important role that art can play in connecting more people with nature, and I kept my eye on the development of this conference.

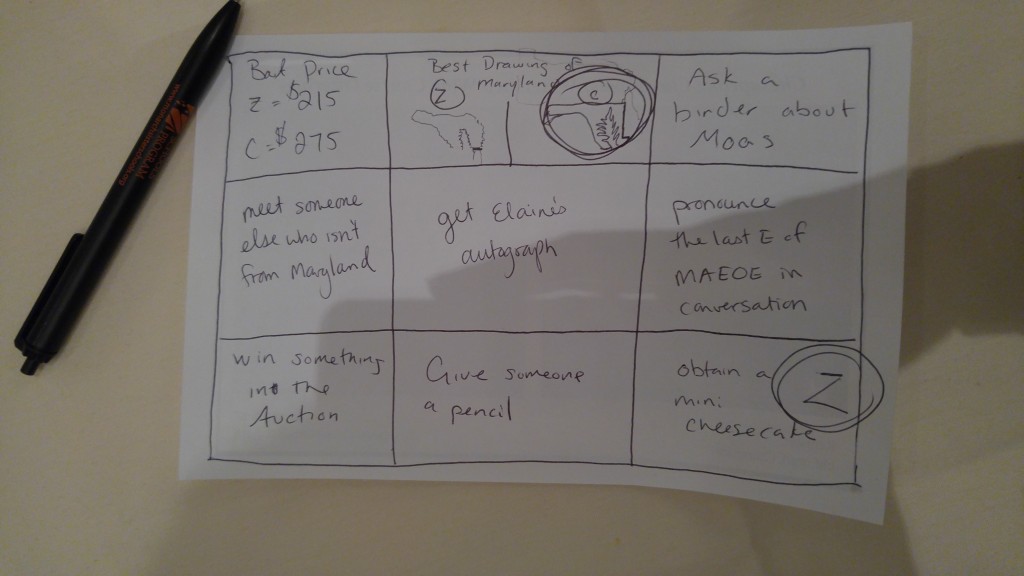

When the call for proposals went out over the summer, the hardest part for me was deciding what facet of the Schuylkill Center’s work would be the best fit for this context. I decided it would be interesting to share the Schuylkill Center’s residency program, LandLab, as a case study for how environmental art residencies can be a rich pathway to integrating professional artists into environmental education efforts. I was thrilled that my abstract was accepted, and I recruited former LandLab artist Zya Levy to co-present with me at this conference. Armed with coffee and bagels, we road-tripped down to Towson, MD early Saturday morning, excited to connect with the hundreds of, we hoped, creatively minded environmental educators at the conference.

We had a great session, which we cheekily titled “The Artist is Out: Art Residencies for Nature & People at Environmental Education Centers.” It was well-attended by a diverse group of environmental educators and nature center staff members from across the country, who engaged in a rich discussion of how residency programs can effectively support artists who want to investigate ecological issues, and how the residency model can operate at an environmental education center. I shared about the process of developing and implementing LandLab, and how we came to structure it in a way that worked for us and our resources. We explored questions environmental education centers should consider if interested in establishing an extended collaboration with an artist. What is an artist residency exactly, and why would a nature center want to have one? What are your goals in engaging with an artist in this way, and what do you mean when you refer to “environmental art”? What are you able to offer an artist in terms of financial support, space, subject matter to engage with, and expertise on your staff?

I think there are few mistakes to be made in the answering of these questions, but many mistakes to be made in not asking them and having clear answers upfront, so we emphasized that there are a wide variety of forms an artist residency can take, at nature centers and beyond. In addition to the nuts and bolts, Zya eloquently shared her own LandLab project and what the experience meant to her and her career; by the end, she had everyone excited about both weaving with and drinking invasive plants.

In addition to our presentation, Zya and I had the opportunity to attend other sessions to experience other centers’ models for integrating the arts into environmental education programming, as well as the chance to connect with other artists and educators pursuing similar work. One highlight for me was a session on a program of Washington College called the Sandbox that supports interdisciplinary collaborations. Through exhibitions, residencies, courses, and more, the program seems to excel at setting the stage for artists and scientists to “play in the same sandbox” together, with often magical results.

One project I couldn’t wait to look into more was WaterLines: RiverBank, where an architect/artist, choreographer, composer, and biologist came together to create and installation and performance at a vacant building on the banks of a river. I also felt envious of the students who got to take the class “Dramatizing Discovery” with Professor Laura Eckelman, a course where they read and analyzed a different science-related play each week. I was intrigued by how she characterized science plays into three categories, those which deal with science in a documentary sense (such as Life of Galileo, which chronicles the life of the title scientist), a thematic sense (like Uncanny Valley, which explores the notion of consciousness in machines and the possibility of immortality), or structurally in the play itself (such as Constellations, which enacts the theory of the multiverse by showing the characters in a multitude of possible realities). Eckelman’s collaboration with a mathematician who studies knot theory was also compelling, and made me realize how little I understand or think about the mathematical properties of light and space.

Stacy Levy’s lunchtime keynote was another high point. I always enjoy hearing Levy speak, not only because she often talks about the Schuylkill Center’s Rain Yard to a broader audience, but because she is one of the most prolific and compelling artists working in the environmental realm today. At this presentation, it was a treat to hear about her recent work in my hometown of Pittsburgh, a human-scale version of the microtopography of shale stream channels in Western Pennsylvania that is equally compelling in wet and dry weather. I was also struck by how she described some of her work in San Antonio in which she creates opportunities for people to experience hydrology with their own body, walking on meandering paths to really feel the flow of a river rather than just learning about stream morphology scientifically.

Playing with scale in the opposite direction, her works that include watershed maps allow people to wander around a miniaturized version of their watershed and locate their homes and other important places along the map. One of the most compelling parts of Levy’s work, to me, is what she describes as showing “not just what nature looks like but what it does.” For an example outside of water, Levy created sculptures that facilitate birds building own habitat in Oregon, capitalizing on the ability of birds to be horticulturalists themselves.

In all, it was deeply refreshing to have the chance to think about how art fits into environmental education with so many vibrant, engaged educators just south of us – I was grateful to be involved in such a wonderful gathering, and hope that the effects ripple out into more robust support of environmental art in Maryland and beyond.