Pennsylvania school kids are still mistakenly taught that our state’s history begins in 1681 with William Penn and the naming of our state, Penn’s Woods. Of course, the land already had a name, Lenapehoking, and it was hardly new: for some 10,000 years before William Penn, the Lenape inhabited Lenapehoking.

On Thursday evening, November 4 at 7:00 p.m., in celebration of Native American Heritage Month, we will present “The Lenape and the Land,” a free virtual conversation among three members of the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania: Chuck “GentleMoon” Demund, Chief of Ceremonies, Shelley DePaul, Chief of Education and Language, and Adam DePaul, the nation’s Storykeeper. This event concludes the our five-part Thursday Night Live series, where visitors have dropped in from as far away as Florida, Maine, and Saskatoon.

The conversation intends to share the extraordinarily surprising story of the Lenape and their relationship to the land.

Living in small towns across the region, the Lenape territory stretched from Maryland and coastal Delaware through eastern Pennsylvania, included all of New Jersey, and swept north deep into upstate New York. It was the Lenape who famously “sold” the island of Manahatta to the Dutch in 1626 (almost 60 years before William Penn was granted Pennsylvania), and the Dutch who built a wall around New Amsterdam to protect themselves from the British and the Lenape; the island of course is Manhattan and Wall Street marks the boundary of that wall.

And the Delaware River of course had a name then as well: Lenapewihittuck. It is appropriate that their tribal name is embedded in the river’s, as the river was the main artery that flowed through Lenapehoking; one writer called it their Main Street. “Delaware” is a name the English bestowed on the river after their Lord de la Warr.

In addition, many sources routinely identify them as the Lenni-Lenape. Adam DePaul notes that “this term is an anglicized grammatical error that basically translates as the ‘original people people.’” Though he acknowledges that though many Lenape identify as either Lenni-Lenape or Delaware, “the best word to use when referring to us is simply ‘Lenape.’”

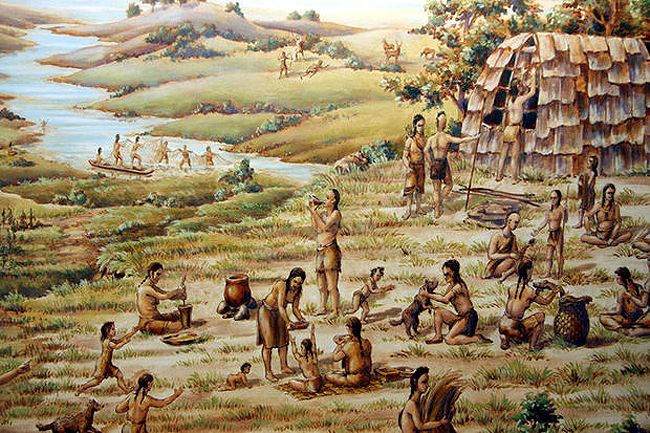

Most accounts of the Lenape– and actually of most Native Americans– present them as living passively on the land, treading lightly, hunting a few animals here and there, using every part of that animal, having little or no impact on the land. Early American writers thus dubbed the New World “pristine,” “untouched,” and that most ridiculously and horribly loaded word, “virgin.” The “noble savage” myth dehumanizes the Lenape as completely as the “fierce warrior” does. All this mythology still permeates our understanding of First Nations, as we never give them their deserving three dimensions. So let’s muddy these waters completely.

Most importantly, Lenapehoking was never a pristine, untouched, virgin forest. Hardly. The big surprise of modern Lenape scholarship, arrived at from studies of both paleoecology and forest ecology, is that the Lenape practiced a highly skilled and remarkably common form of fire ecology, one actively practiced by many indigenous people across the Americas.

In short, they routinely burned Lenapehoking. The forest was continuously sculpted by native hands to create a wide variety of desired benefits. Most importantly, fire favored the growth of oaks, chestnuts, hickories, and walnuts, trees that offered so many other benefits, especially mast, the forester’s name for nut production. Blueberry bushes, the fruit so nutritious, also respond to burning, producing more fruit in the year right after a fire.

“Fire enhanced their production of mast and fruit,” says Penn State forest ecologist Marc David Abrams, who has been researching fire ecology for 40 years, “not only to feed themselves, but to feed the animals they were hunting; it was a win-win.” More mast meant more deer, turkeys, passenger pigeons, rabbits, and bears, animals they wanted and needed for food, bones, fur, and feathers.

But the benefits don’t stop there. The ash resulting from fire was nutrient-rich, offering many plants the ability to grow healthy and fast, and some of the plants that came back after a burn were medicinal plants with important healing properties. Fire cleared out the underbrush, allowing hunters to cover more land more easily while giving them better sightlines to find and shoot prey. Ticks and other harmful pests overwintering in the undergrowth were even killed in a spring fire, and these fires prevented the buildup of too much brush on the ground, which would lead to major conflagrations.

Of course, these were not the wildfires making headlines in so many climate-challenged places. No. These more modest fires quickly burn off the leaf litter, the moist soil preventing the fire from completely destroying the soil’s upper layers. The fire moves quickly through dry leaf litter, and taller trees keep their branches well above the flames, the thick bark protecting the tree charring but surviving.

Acorns and chestnuts cannot sprout and grow underneath their own dense canopy; they require more sunlight hitting the soil than a dense forest offers. Thus, burning cleared out gaps in the forest for acorns and nuts to sprout and grow. If the Lenape did not burn, the forest would have matured, and growing underneath the oak trees would be the late-stage successional trees of maple, beech, birch, and hemlock, fine trees all, but with lower wildlife value and fewer nuts for themselves. So the Lenape kept forests frozen in mid-succession. Dr. Abrams researched an old growth forest in West Virginia that was being logged, and found burn scars in many of the cut stumps indicating indigenous people would burn a section of forest every 8-10 years or so, a number backed up by research from others in the field.

So Penn’s Woods neither belonged to Penn nor was a pristine wilderness. Lenapehoking instead was a highly managed and yet sustainable forest artificially kept in a lower stage of succession in many areas, propping up the plants the Lenape needed nearby, especially chestnuts and oaks. Among their many qualities, the Lenape were exceptional ecologists continuously molding the land to fit their lifestyle.

That’s just the beginning of the story; we hope you’ll register for “The Lenape and the Land,” and learn more about the first Philadelphians.

By Mike Weilbacher, Executive Director

This is such important information about the history of our land and how to manage it sustainably. Can’t wait to learn more.

https://youtu.be/hVnun_bKTwo

Was this event recorded?

There is a link at the beginning of this blog post.

https://youtu.be/hVnun_bKTwo