By Christina Catanese, Director of Environmental Art

What’s in a name? It’s one of the first things we ask someone, but can be quickly forgotten. It’s often given to us by others, yet is expected to serve as a distillation of our identity. Who gets to decide a name is a question layered with power dynamics, whether it be people, places, organisms, or ecosystems.

Despite these complexities, in a 2017 New York Times op-ed, Akiko Busch wrote, “Giving something a name is the first step in taking care of it.” Thinking of bodies of water, a name is an opening, a prelude, a microcosm, a way to be known—a first step on the pathway to meaningful connections between people and nature.

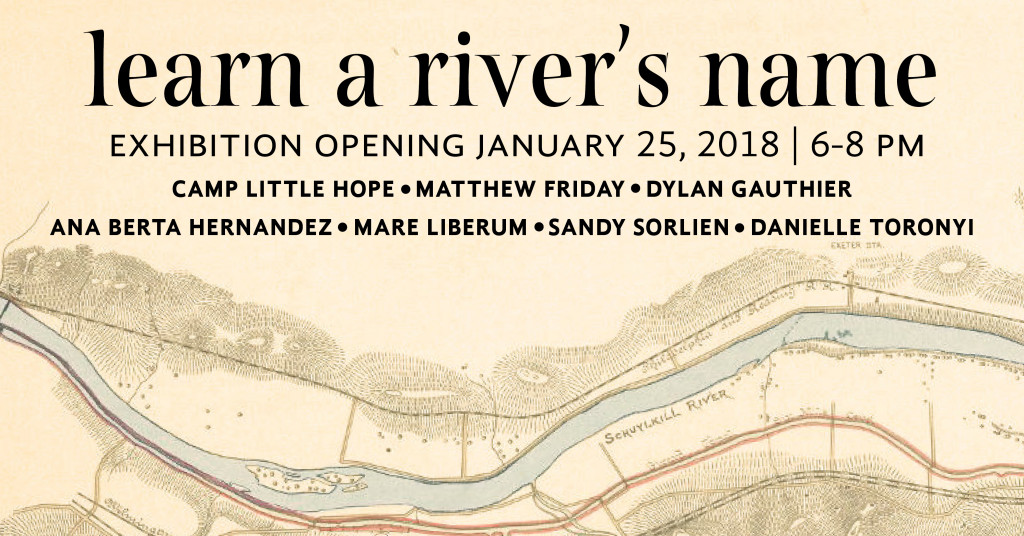

This winter, the Schuylkill Center will open Learn a River’s Name, a new exhibition in our art gallery. It’s a group of seven projects guided by this question: how can art help us to know a river’s name, to not only value it but know it, and therefore to seek to steward it? With a focus on water bodies in the Mid-Atlantic region, seven artists explore rivers and streams within driving distance of the Schuylkill Center—the Schuylkill, Delaware, Brandywine, and Hudson Rivers.

Learn a River’s Name consists of artworks and art investigations that provide inroads to getting to know our rivers. It includes projects that incorporate deep and focused engagement with a particular river, watershed, or stream. Roxborough artist Sandy Sorlien spent years bushwhacking and photographing to document the remains of the 200-year-old Schuylkill River navigation system.

Her complete collection is the only contemporary capturing of this historic system, from which she presents selected photos and maps in our gallery.

Featured alongside fully actualized investigations are relics from artistic processes by which an artist got to know a river in ways that might feel a lot like getting to know a person. Dylan Gauthier recently completed a yearlong residency at the Brandywine River Museum and will present various outcomes of his residency along with schematic mappings of the river and his thinking.

Learn a River’s Name also includes art works that reveal something unseen about a water body’s characteristics, its essential nature. Danielle Toronyi turns real-time Schuylkill River data into sound, and Matthew Friday creates paintings and diagrams with materials from the Hudson River itself—plants growing along the river along with water pollutants like PCBs.

Soaring above it all will be a 16-foot-long boat created and sailed on the Lower Schuylkill by artist collective Mare Liberum in collaboration with students from Haverford College, and painted by Chloe Wang with elements of the river’s tidal cycle and animal inhabitants.

Alongside the artists’ works (which also include Ana Berta Hernandez’s response to fracking in the Delaware watershed and local artist collective Camp Little Hope’s reflection on sea level rise and Philadelphia neighborhoods), the gallery will be peppered with historical information on how regional rivers came by their current names—and what names they were once known by, but we no longer use. Did you know that the Delaware River was first known to the Lenape people as makerisk-kitton, or the great tidewater river, then to early Swedish and Dutch settlers as simply South River, before being named for Sir Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, an English politician who served as governor of the colony of Virginia until he died at sea in 1618?

Learn a River’s Name is an open invitation to better know a nearby river or creek, a call to action to know not just its name, but its features, its needs, and how we can be good neighbors.

Celebrated environmental writer Wendell Berry wrote:

“People exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love, and to defend what we love we need a particularizing language, for we love what we particularly know.”

Help us celebrate the opening of Learn a River’s Name (and the beginning of the Schuylkill Center’s Year of Water) with a reception on Thursday, January 25 at 6 pm. Enjoy light refreshments in the gallery and a guided tour of the exhibition. Learn a River’s Name will be on view through April 21st.

Christina Catanese directs the Schuylkill Center’s Environmental Art program, tweets @SchuylkillArt, and can be reached at [email protected]. For more information on the environmental art program, visit www.schuylkillcenter.org.