By Christina Catanese, Director of Environmental Art

I recently got to attend a lecture at Swarthmore College’s List Gallery given by Stacy Levy, one of the most exciting environmental artists working today. Titled “Constructing Nature: What Art Reveals,” Levy’s talk (video here) touched on her approach to environmental art, some of her past pieces (including one we’re lucky to have onsite here at the Schuylkill Center), and two new pieces that were unveiled that night at Swarthmore.

Listening to Levy, it’s hard not to be struck by all that environmental art is and has the potential to be. She talked about art as an indicator of the processes and changes happening around us. Art can paint a clearer picture than what we get by looking at charts or graphs which present the same data. Levy’s Bushkill Curtain, by means of a few strings of buoys hanging off of a bridge, reveals much about the hydrologic cycle. Bushkill Curtain finds a new way to show the tumultuous flow of the Easton, PA river during storms, the elevated but calm water levels afterwards, and the river’s baseline conditions in drier weather.

Levy also talked about environmental art traditionally being “in, but not of, the environment” – pieces that exist outdoors but aren’t “doing anything” in that space, per se. For example, see Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, what Levy called “the Mona Lisa of Environmental Art,” or the unexpected forms created by Andy Goldsworthy.

Pieces like this are spectacular to look at, but can art do more? Levy and many other cutting-edge environmental artists think so, and have explored this angle: art can work for the landscape itself, actually doing the restoration needed in a damaged forest or purifying a polluted stream.

In this vein, yet in homage to Spiral Jetty, Levy described her Spiral Wetland, a floating, constructed wetland in a spiral form that helps to remove excess nutrients from the water body it floats in. She also touched on Rain Yard, a sculptural installation at the Schuylkill Center that harvests and redirects the rain water that falls on our roof, giving it time and space to infiltrate (aside: Rain Yard is on permanent view here and we welcome anyone to come see it!). These are just a few ways that art can be put to work for the environment.

In unveiling the two new pieces at Swarthmore, Levy went in depth on how these pieces came about, an aspect of art that viewers usually aren’t privy to. Revealing this process gives an appreciation to how much work goes into a completed piece, and not just on the artist’s part. To create work like Levy’s – to build what she calls “a space, not an object” – many hands are needed, which is why her work is almost always a community engagement process as much as an artistic one.

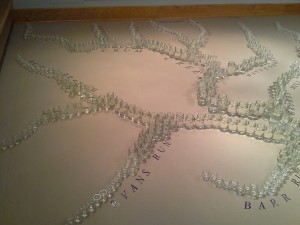

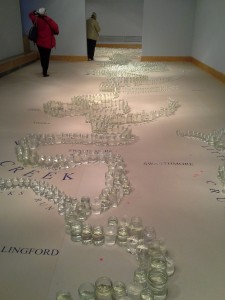

Both of the new works conjure up Crum Creek, a stream that is largely unseen, though it flows through Swarthmore’s campus. Waterways is a map of Crum Creek, constructed on the List gallery floor with many small clear glass and plastic vessels salvaged from the waste stream. Each glass is filled with water gathered by Levy and Swarthmore volunteers from around the watershed, and each reconstructed tributary contains water sampled from that stream. Viewers were invited to place colored dots where they live in the watershed, and to walk around the gallery without shoes on – an unexpected delight! Though we can’t judge water quality solely by sight, I was struck by the color gradation of the water samples as the water “flowed” downstream.

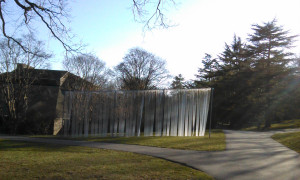

Crum Creek Meander, the second new work, is a long-term piece on a centrally located green on campus, where hundreds of students and faculty will encounter it every day. Its meandering form calls to mind the unseen river, alluding to a past tributary that may have existed. Ten foot tall strips of clear and black vinyl create a reflective barrier, yet the work is permeable visually and physically. The work reimagines natural forms with industrial materials. We live with manmade materials and grapple with their impacts every day, but here, they are reimagined and juxtaposed with the organic form of a river. With the shape and the movement of the piece, the vinyl manages to give a sense of water despite itself being entirely dry and wholly unnatural.

Crum Creek Meander, the second new work, is a long-term piece on a centrally located green on campus, where hundreds of students and faculty will encounter it every day. Its meandering form calls to mind the unseen river, alluding to a past tributary that may have existed. Ten foot tall strips of clear and black vinyl create a reflective barrier, yet the work is permeable visually and physically. The work reimagines natural forms with industrial materials. We live with manmade materials and grapple with their impacts every day, but here, they are reimagined and juxtaposed with the organic form of a river. With the shape and the movement of the piece, the vinyl manages to give a sense of water despite itself being entirely dry and wholly unnatural.

I walked through the meander after Levy’s lecture, and felt transported and hidden within its curves. On the quiet, cold evening on campus, the gentle wind fluttered the curtain of the sculpture against me, an unexpected physical encounter to complement a new appreciation for observation, process, and what art can be.