Lauren Bobyock, Environmental Art and Communications Intern

What does community mean to you? Here at the Schuylkill Center, community means connection. We offer a wide range of ways for humans of all ages and backgrounds to engage with nature—whether you are spending time with your family outside at our weekly Schuylkill Saturdays, or attending our Meigs Environmental Leadership Award ceremonies to learn about strides our community members take to further environmentalism. Our community contributes to the Schuylkill Center in a variety of ways, and we are excited to honor all friends, members, volunteers, and staff in an exciting and creative way this winter.

A crucial aspect of the Schuylkill Center is our Environmental Art department. Using art, we are able to seamlessly pair science with physical movement, history with inventive up-cycling, and math with textiles. Art bridges the gap between all facets of life, and we especially value how it is connected to the environment.

Our gallery has been the home for a vast number of environmental art projects since its expansion in 2013. We’ve incorporated animals, mythology, botany, kinetic energy, architecture, geology, fashion, local history, and the Schuylkill Center itself as topics for many environmental projects. But none of these projects were created alone. Contributions from nature and humans made each gallery piece possible.

Hayley Crawford’s “Love leaves.” uses materials from nature to display a love for local surroundings. Displayed in Community, 2017.

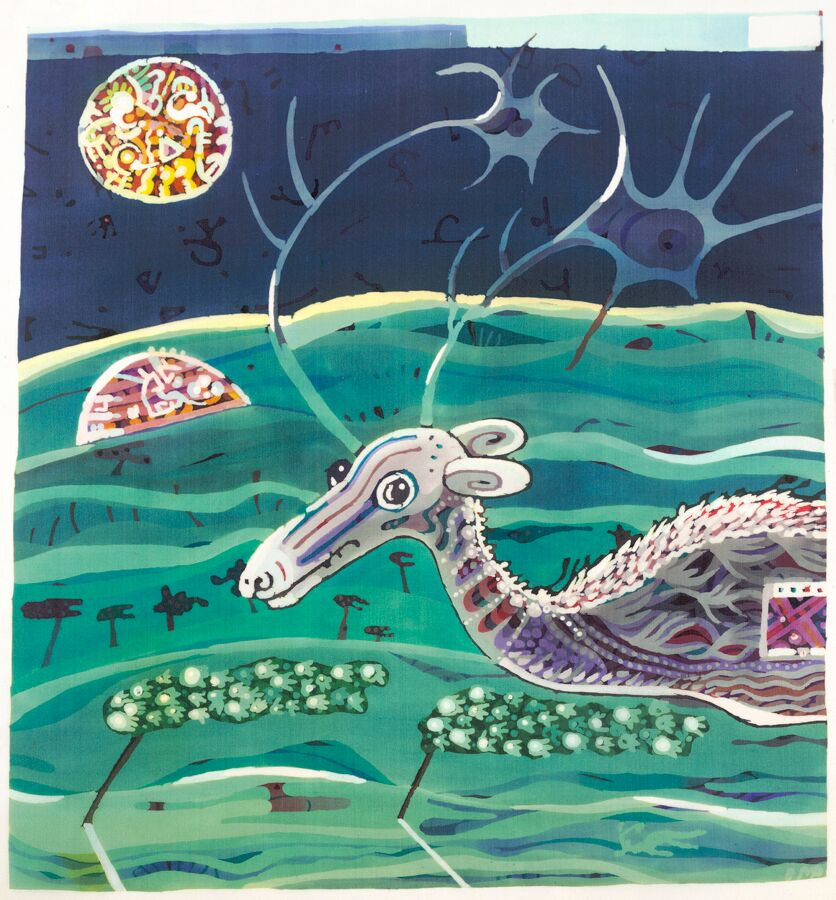

Laura’s “Un Cerf Magique” captures a moment in nature using illuminating colors highlighting the magic and fantastical scenes found outside. Displayed in Community, 2017.

Art connects people to each other and to the environment, and these connections contribute to creating the invaluable community that we are lucky enough to consider a Schuylkill Center family. For the second time (after an extraordinary success), we are excited to invite our community to fill the gallery with their own works this February as we celebrate your dedication to the Schuylkill Center and your creative works. Community, this unique upcoming exhibition, will feature artwork of anyone and everyone involved with the Schuylkill Center. We welcome all art mediums—clay, weaving, photography, woodwork, painting, dance—the possibilities are endless. Read more about our guidelines and how to submit work here (deadline January 6).

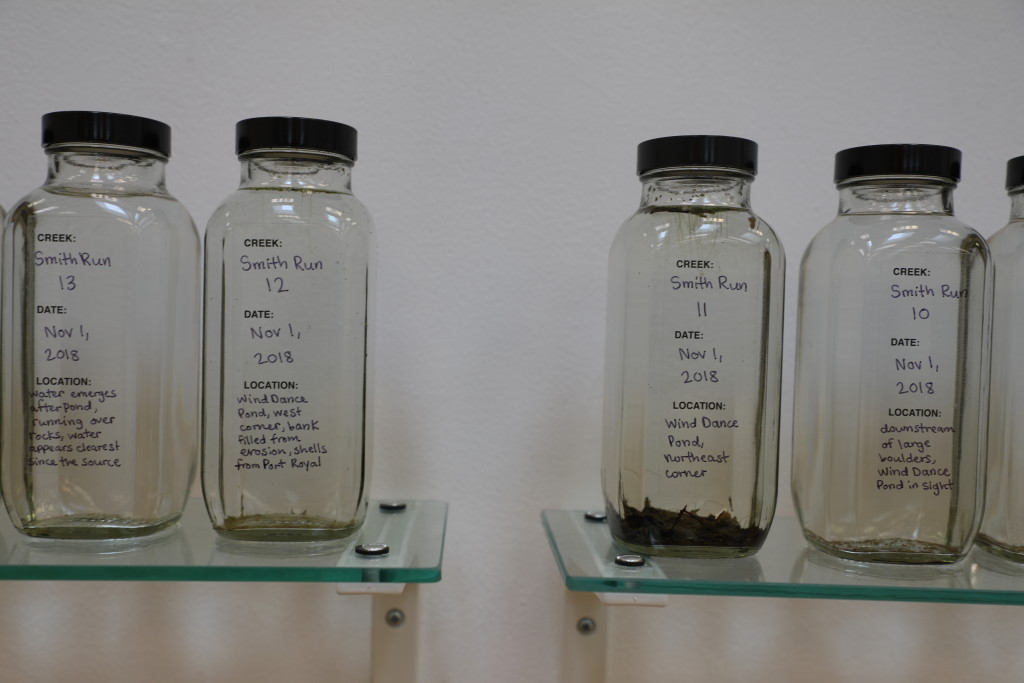

Kelsey Wimmenaur’s “Water Series 2/3” uses bodies of water as inspiration to express the comfort received from water in nature. Displayed in Community, 2017.

When previously done in 2017, we saw this exhibit bring the Schuylkill Center community to life like never before. Barriers were broken and expectations exceeded, and we look forward to seeing what our community has in store for us this time around. Community will be on view in the gallery from February 21 through April 27, 2019. An opening reception will be held on February 21, 2019.