By Aaliyah Green Ross, Director of Education

By Aaliyah Green Ross, Director of Education

Dr. Chris Renjilian, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) pediatrician, sees nature and play as essential parts of his primary care practice. But he worries that his guidance isn’t always enough. NaturePHL is about to change that. With NaturePHL, pediatricians like Dr. Renjilian will be prescribing nature to children across the city.

This summer marks the official launch of NaturePHL, a collaborative program that helps Philadelphia children and families achieve better health through outdoor activity. It’s a collaborative  involving four core partners – the Schuylkill Center, CHOP, Philadelphia Parks and Recreation, and the United States Forest Service. It’s a new website indexing all parks, trails, and green spaces in the city, so anyone can search their neighborhood for places to be outdoors. But NaturePHL is most importantly a toolkit that pediatricians will use to prescribe outdoor activity and time in nature. This innovative program is the first of its kind in Pennsylvania.

involving four core partners – the Schuylkill Center, CHOP, Philadelphia Parks and Recreation, and the United States Forest Service. It’s a new website indexing all parks, trails, and green spaces in the city, so anyone can search their neighborhood for places to be outdoors. But NaturePHL is most importantly a toolkit that pediatricians will use to prescribe outdoor activity and time in nature. This innovative program is the first of its kind in Pennsylvania.

The program will launch in two CHOP clinics, ultimately reaching 21,000 children over a three-year pilot. This intervention is dearly needed to reconnect families with the outdoors.

The last several decades have seen a substantial shift in the way most U.S. children interact with both natural and built environments. One recent study says that for children ages 6-17, the average weekly time spent engaged in outdoor activities decreased from one hour and 40 minutes in 1982 to only 50 minutes in 2003; current trends suggest the amount is even lower today. In short, childhood has moved indoors, with significant health impacts.

The same study concluded that time spent looking at screens and other sedentary behaviors dramatically increased over the same time period, a trend that the Centers for Disease Control has linked to the rise in childhood obesity rates. Children who are sedentary and obese are more likely to suffer from a range of medical problems, including high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, asthma, sleep apnea, and psychological issues including anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem.

The same study concluded that time spent looking at screens and other sedentary behaviors dramatically increased over the same time period, a trend that the Centers for Disease Control has linked to the rise in childhood obesity rates. Children who are sedentary and obese are more likely to suffer from a range of medical problems, including high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, asthma, sleep apnea, and psychological issues including anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem.

But there are solutions: Active, outdoor play has been shown to have positive effects on several health indicators, from reduced stress and better sleep to improved focus and self-control. A 2009 study by the EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research found lower incidence of 15 diseases—including depression, anxiety, heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and migraines—in people who lived within a half mile of green space.

The potential to leverage nature and outdoor activity for betting health is what first drew the Schuylkill Center to reach out to CHOP in 2013 and open the conversation that, four years later became NaturePHL. The tools developed for NaturePHL will aid physicians in helping their patients change sedentary and indoor behaviors for free play and time outdoors. And there is plenty of space to do so.

Of Philadelphia’s nearly 91,000 acres, green spaces account for over 10,000 acres, about 12% of the city’s land. Despite the abundance of open spaces to engage in outdoor play, many of our city’s kids don’t get the daily 60 minutes of physical activity recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The reasons for this are many: lack of time, safety concerns, and general unawareness of local green spaces were among the most common barriers identified by families participating in NaturePHL’s focus groups.

Knowing that connecting more children with better health through nature would depend on successfully overcoming these barriers, a NaturePHL team of pediatricians developed a way to integrate a discussion of outdoor activity into annual well-child visits. If a clinician determines that a child needs to spend more time outdoors, they will offer counseling and issue a prescription to play at a park, go for a bike ride, or take a walk around their neighborhood, among other outdoor activities. To make it easier for parents, pediatricians will offer educational materials with suggested activities and strategies to make spending time outside more feasible for their family.

“Our city’s many vibrant parks and green spaces can be a part of every child’s prescription for health and wellness,” says Dr. Khoi Dang, a pediatrician based in the CHOP South Philadelphia primary care clinic who has been deeply involved in planning and developing NaturePHL.

But providing a toolkit to talk about outdoor activity and issue nature prescriptions alone won’t be sufficient to achieve the program’s goals. We also need to support patient families in their efforts to fulfill prescriptions. This is where the Nature Navigator comes in.

Like social workers who help asthma patients adhere to recommendations, the Nature Navigators are community health workers trained to serve as liaisons between clinics and patients, helping patients access health services and motivating them to practice healthy behaviors. We’re excited to be hiring one Nature Navigator this summer, who will follow up with patient families receiving nature prescriptions to help them spend more time outdoors, and will even meet with families to lead children in outdoor activities to help make nature time part of their daily lives.

This is central to the Schuylkill Center’s work. In our vision statement we imagine “a world where all people learn, play, and grow with nature as a part of their everyday lives.” With a program like NaturePHL, we’re able to reach new audiences and connect many thousands of children with nature in a new way. At the same time, the program will help the Schuylkill Center reach a more ethnically and economically diverse group of people. CHOP’s Cobbs Creek and Karabots primary care clinics serve a largely African-American client base – a demographic that hasn’t traditionally participated in our programs much.

In addition, the Schuylkill Center and Parks and Recreation are creating new programs designed to help families be in nature. Some will be NaturePHL-branded, with clinicians leading hikes or nature play, at parks and green spaces around the city.

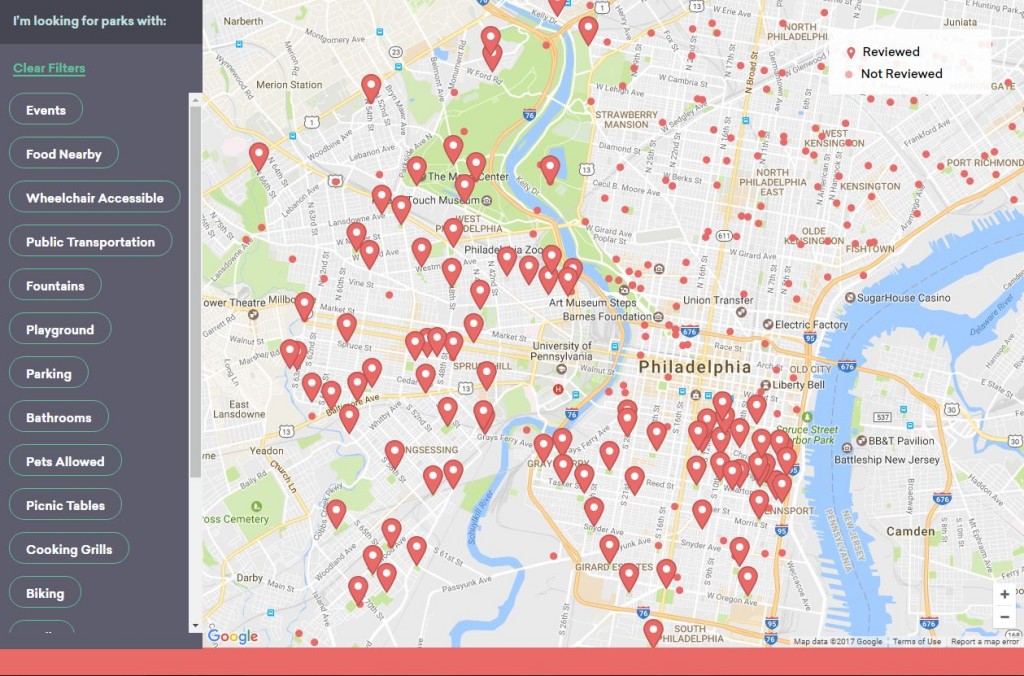

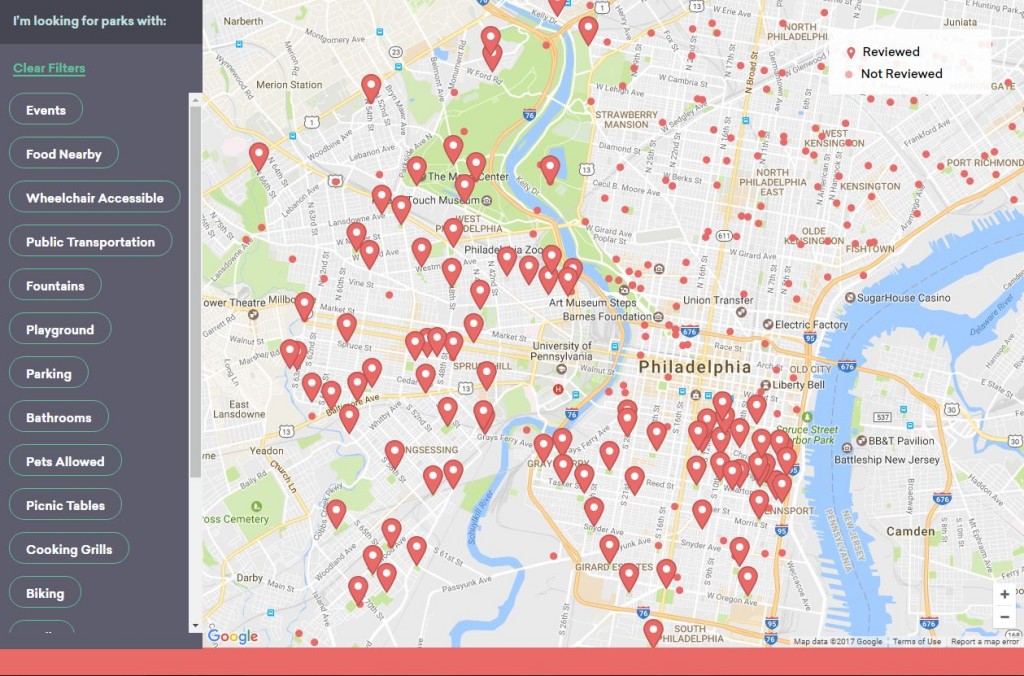

These events will be searchable from the NaturePHL website, naturephl.org, developed by local design studio P’unk Ave, making it easier for doctors and patients to identify ways to spend time outside. At the same time, the website’s reach goes beyond the children receiving nature prescriptions. For anyone looking to enjoy time outdoors in Philadelphia, naturephl.org offers a way to search parks by amenities such as events, wheelchair and stroller accessibility, nearby SEPTA routes, playground equipment, picnic tables, and other features.

The website also provides a unique platform for partnerships with several community organizations, adding value to the site and broadening the program’s reach. Partnering with the Clean Air Council’s new program, Go Philly Go, NaturePHL will include multimodal transportation options and directions on each park page. Another collaboration with Philly Fun Guide allows us to list events happening at parks and green spaces throughout the city, elevating opportunities for patient families to engage in outdoor activities.

The website also provides a unique platform for partnerships with several community organizations, adding value to the site and broadening the program’s reach. Partnering with the Clean Air Council’s new program, Go Philly Go, NaturePHL will include multimodal transportation options and directions on each park page. Another collaboration with Philly Fun Guide allows us to list events happening at parks and green spaces throughout the city, elevating opportunities for patient families to engage in outdoor activities.

Above all, NaturePHL is at the frontier of environmental education and healthcare. Integrating these two seemingly disparate sectors, the program will also serve as a national model.

A press conference to announce the official launch of NaturePHL will be held on Wednesday, July 26 at Cobbs Creek Recreation Center, and the first nature prescriptions will be issued at CHOP’s Cobbs Creek and Roxborough primary care clinics starting August 1. We are thrilled to see this program come into fruition after nearly four years of planning, research, and collaboration. We invite you to join in by visiting www.naturephl.org to plan your next family nature outing!

NaturePHL is supported in part by the Barra Foundation and the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. An excerpt from this piece was published in our summer newsletter in June 2017.

About the Author

About the Author

Aaliyah Ross joined the Schuylkill Center as Director of Education in March. She enjoys flipping rocks in Smith’s Run while looking for salamanders, and discovering new parks to explore with her 4-year old daughter.

I am good at learning. In fact, I might even go as far as to say it is an ongoing discovery process. I figure things out, consider many different perspectives, and question everything while looking deeply into why. I’m finding my passion and sharing it with others. I am going to make the world better because of it. It seems that embodying these qualities in pursuit of knowledge may be one of the truest keys to life.

I am good at learning. In fact, I might even go as far as to say it is an ongoing discovery process. I figure things out, consider many different perspectives, and question everything while looking deeply into why. I’m finding my passion and sharing it with others. I am going to make the world better because of it. It seems that embodying these qualities in pursuit of knowledge may be one of the truest keys to life.

We can address these problems by improving the soil and providing the roots of trees with a healthy environment to grow and develop. In our Fox Glen restoration site, as we planted new trees we covered the ground around them with wood chips to help the roots retain moisture. The wood chips will break down over time and add to the organic content of the soil.

We can address these problems by improving the soil and providing the roots of trees with a healthy environment to grow and develop. In our Fox Glen restoration site, as we planted new trees we covered the ground around them with wood chips to help the roots retain moisture. The wood chips will break down over time and add to the organic content of the soil.  Andrew has a master’s degree in landscape architecture and ecological restoration from Temple University. He hiked the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine in 2005-2006.

Andrew has a master’s degree in landscape architecture and ecological restoration from Temple University. He hiked the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine in 2005-2006.

For Carver, performing is a way that she can connect with others. “I love singing with other people,” she says, “That’s my joy.” Carver now sings with

For Carver, performing is a way that she can connect with others. “I love singing with other people,” she says, “That’s my joy.” Carver now sings with

By Aaliyah Green Ross, Director of Education

By Aaliyah Green Ross, Director of Education involving four core partners – the Schuylkill Center, CHOP,

involving four core partners – the Schuylkill Center, CHOP,  The same study concluded that time spent looking at screens and other sedentary behaviors dramatically increased over the same time period, a trend that the Centers for Disease Control has linked to the rise in childhood obesity rates. Children who are sedentary and obese are more likely to suffer from a range of medical problems, including high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, asthma, sleep apnea, and psychological issues including anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem.

The same study concluded that time spent looking at screens and other sedentary behaviors dramatically increased over the same time period, a trend that the Centers for Disease Control has linked to the rise in childhood obesity rates. Children who are sedentary and obese are more likely to suffer from a range of medical problems, including high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, asthma, sleep apnea, and psychological issues including anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem.

About the Author

About the Author