by Anna Lehr Mueser, Manager of Communications & Digital Strategy and Jenny Ryder, Communications Coordinator

There’s been plenty of discussion, and some research, about the overlap between LGBTQ people (and activists) and environmentally conscious people (and activists). So, today we’re talking especially about environmental leadership – about people from the LGBTQ community who have stood up to be leaders for climate justice, for environmental science, even the woman who gave modern American environmentalism its birth.

The people who worked to ban DDT and protect nesting birds, who helped establish the Environmental Protection Agency, who help communities find the resources to relocate before rising seas take their homes, share something with the people who fought to remove homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association list of mental disorders, who lobbied and marched for recognition and legal protection, who stood up for pride, rather than shame.

What they share is a vision of a better world, a world where people can lead their lives safely and in community. Today, we’re celebrating a handful of LGBTQ environmental leaders. So, in honor of Pride Month, a few LGBTQ environmental leaders of note:

Ceci Pineda is a gender non-conforming organizer with the Audre Lorde Project in New York City, “a community organizing center run for and by lesbian, gay, bisexual, two spirit, trans, and gender non-conforming people of color.” On behalf of the project, they drafted a letter of solidarity with the climate justice movement, drawing attention to the less-talked-about environmental justice movement led by people of color most disproportionately affected by climate change. They are a graduate of Brown University and founder of RADIKO, which “envisions an inclusive climate justice movement led for and by those who are most impacted by climate change, rooted on a shared value system that honors life,” and provides tools for educators to run climate justice workshops specifically for communities of queer and trans people of color living on the frontlines of climate violence.

Source: http://gchd.us/primary-care-clinic/

In Flint, Michigan, a LGBTQ organizaiton, Wellness AIDS Services, is responding to the water crisis that has left residents with no clean drinking water for the last three years by offering a safe place for people to pick up clean bottled water. CEO Stevi Atkins, who runs the only HIV center in the county, works with many LGBTQ people with compromised immune systems and wanted to give the queer community barrier-free access to drinking water. Nayyirah Shariff , director of Flint Rising, says being LGBTQ is so stigmatized in Flint that there is a need for a safe space where residents can pick up clean water. Many transgender residents feel vulnerable or targeted when asked to show ID (oftentimes, one’s gender presentation doesn’t match the marker on their driver’s license), answer the door, or enter churches, out of which most crisis-response water distribution centers are running. Wellness AIDS is addressing environmental injustice head-on in one of the most marginalized cities in the country by securing not only responding to basic health and wellness, but making safe space amid crisis to do so. They handed out 1,000 cases of water last year.

From FUTURE FEMINISM, a 2014 exhibition by ANOHNI, Johanna Constantine, Kembra Pfahler, Bianca Casady and Sierra Casady (pulled from ANHONI’s Facebook page)

Same as above

In November 2016, transgender musician and artist Anhoni Hegarty (of Antony & the Johnsons fame) released “4 Degrees,” a single off her debut solo album, Hopelessness, on the day before the United Nation’s Climate Change Conference in Paris. The title of the track references a study that revealed the consequences of a predicted 4C degree global temperature increase by the end of the century. In a Facebook post accompanying the release, she stated: “In solidarity with the climate conference in Paris, giving myself a good hard look, not my aspirations but my behaviors, revealing my insidious complicity. It’s a whole new world. Let’s be brave and tell the truth as much as we can.”

Paul Gestos, National Coodinator for People’s Climate Movement, and co-author of Tools for Radical Democracy: How to Organize for Power in your Community is a queer New York-based climate activist. Gestos is a graduate of Rutgers University, and teaches Community Organizing at the Columbia University School of Social Work. He was one of the folks behind both the People’s Climate March on the eve of the UN Climate Summit in 2014 and the April 29th March for Climate, Jobs, and Justice in DC. Follow him on Twitter here.

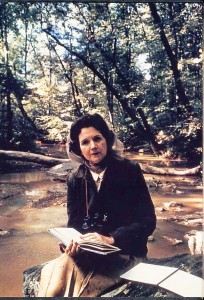

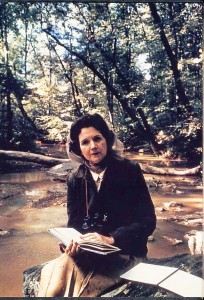

Source: Google images, Alfred Eisenstaedt

Lastly, this post couldn’t go without a shout-out to the marine biologist who kickstarted the modern environmental movement, Rachel Carson, with her groundbreaking work, Silent Spring in 1962. Although she was never officially “out,” much of the critical backlash she got from speaking her truth called her a “spinster”– a subtle derogatory way of insinuating homosexuality. With so many attacks from the pesticide industry, among others following her controversial publication, it’s no wonder she stayed closeted. Shortly before her death of breast cancer, Carson and her longtime friend and neighbor, Dorothy Freeman, destroyed hundreds of letters between them. They had an intimate 11-year relationship, and the remaining correspondence paints a picture of their private lives in a book released by Freeman in 1996, Always, Rachel. Although Dorothy Freeman was married, these letters have led us to conclude that the mother of the modern American environmental movement was probably gay.

The stigma of being queer necessitates an ability to nourish a safe and loving environment in social, home, and work spaces. It’s no wonder why so many LGBTQ people have extended this understanding and way of life to environmental activism, where the goal is to create safe and sustainable spaces for all forms of life. Sustainability is who we are, to survive– not a whole separate thing.